One week before the first dress rehearsal, the world premiere of “The Golem of Prague” was canceled.

The cast and crew of this new opera work, three years in the making, were preparing to take the stage at the Hippodrome State Theatre in March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic forced a change in plans.

"Heartbroken would be the most appropriate word," UF Opera Theatre Director Tony Offerle said about breaking the news to the cast. "But I was still hopeful that there would be a way to pull it off. As it became evident that we weren't going to be able to do it live or at the Hippodrome, we had to radically rethink our approach."

Inspired by the one-act, made-for-television operas of the 1950s, he started making calls.

One of the first people Offerle reached out to was Dr. James Oliverio, director of the UF Digital Worlds Institute. Oliverio had first heard the news of the canceled opera on the radio and said he felt awful for the student performers and the composer Dr. Paul Richards of the UF School of Music.

“As a composer myself, I understood what it’s like to create a large-scale work and how disappointed everyone must have been to have it canceled,” Oliverio said. “I just knew we had to do something.”

Ocala Symphony director Matt Wardell, who had already begun rehearsing for the live production, was excited about the idea of conducting the orchestra for a studio recording.

Over the summer, Offerle invited numerous other entities to join the production. This resulted in a multi-level partnership that would ultimately bring together nine UF departments and community collaborators to turn the stage production into a film.

In a socially distanced pandemic, virtual productions may not seem so strange. But as production manager Austin Gresham pointed out, it was new for the UF opera program.

“Creating films isn’t a new concept. People do it all the time,” Gresham said. “But we don’t do it all the time. It’s not our forte or our focus. So transitioning from the live stage version to how we do the film version was a big learning curve for a lot of us.”

At the time, the School of Music was following guidelines that recommended singers maintain 16 feet of distance, as opposed to the more common six-foot social distancing standards many became accustomed to.

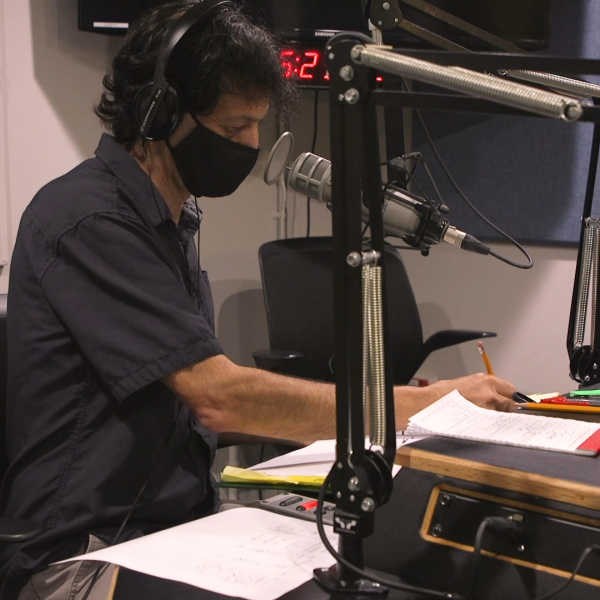

To achieve this, the singers were recorded in the WUFT radio studios in the College of Journalism and Communications. Then, the singers lip-synced to their pre-recorded tracks on stage, to avoid vocal projection that would have required additional distancing.

“We did a lot of research and had discussions with the UF epidemiologists and the folks who are overseeing all of the pandemic protocols at UF, and this was deemed to be a safe way of approaching it,” Offerle said.

The Digital Worlds Institute stepped in to film, edit, and produce the final film.

“It might have been the longest edit of my life,” said Darius Brown, the lead producer and a lecturer at Digital Worlds.

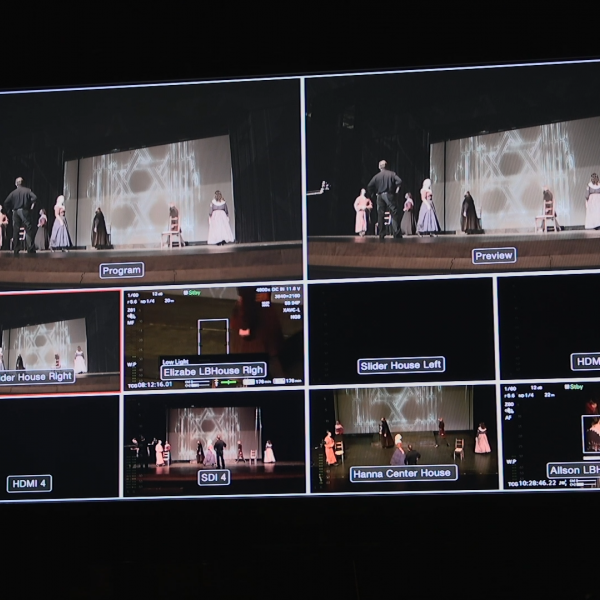

During filming, Brown directed and communicated with seven camera operators while collaborating with Offerle and Richards on how the story should be perceived through a film.

“In theatre, you can look around and take what you want from the performance,” Brown said. “But in cinematography, we are all looking through the same lens and the same framing. Trying to get that understanding established early on was my biggest priority. We needed to focus on what everybody needs to interpret this story as.”

Filming took place at the Curtis M. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts after UF Provost Joseph Glover suggested that the opera program partner with UF Performing Arts, who had recently acquired new camera and recording equipment to present their upcoming season virtually.

Original stage directions and blocking had to be rewritten to accommodate safety precautions. While the prerecorded music allowed singers to be unmasked while lip-syncing, typical six-feet social distancing was still required. An ensemble of singers was also removed from the production.

For the singers, lip-syncing was an unusual challenge. Connor Behrmann, who played Isaac and Emperor Rudolph II, said the performers had less than two weeks to review their pre-recorded tracks before filming began.

“It was a really weird experience,” Behrmann said, “because I’m used to singing along with the radio in the car but when it’s yourself, it’s the decision you made at that time. The Connor that made the decision at that time wins.”

Projection art, designed by Professor Michael Clark was used to set the scene and communicate important plot points. He was originally involved in the staged production at the Hippodrome, but reimagining this for film was a new hurdle.

“We needed to not only understand how the projection element would work but how the overall staging might work,” he said. “We needed to figure out a way to integrate the scenographic information to the cinematographers.”

Clark has worked in a variety of broadcast and film productions, but he said this production felt like a combination of multiple formats.

“We had the cameras from a sporting event with eight or nine things happening at once on stage, a prerecorded and lip-synced opera, and a broadcast event as if we were doing a major award show,” he said, “all superimposed together.”

“The Golem of Prague” is an original work, written by Dr. Paul Richards, composer and professor in the School of Music. The story pulls inspiration from the legend of the Golem, a creature made from clay and brought to life by a rabbi to protect Prague's 16th-century ghetto from persecution.

Richards grew up with this story and used to read a children’s book based on the legend to his kids when they were little, he said.

The major inspiration to compose the opera came to Richards after a trip to Prague. He was visiting the city for a recording session and decided to visit the Jewish quarter, where the Golem myth was quite prominent.

“There is a temple where supposedly the Golem’s body still remains,” he said. “It is a big part of the mythology of the place.”

He also visited a Holocaust museum where he found a song that someone had written while they were forced to live in a concentration camp.

“There was something about seeing an old story of oppression coupled with a somewhat more recent story of oppression that just made me feel like it was an important topic to explore,” Richard said.

The opera film made its world premiere screening on October 16 and has since had over 500 views online.

"When I first envisioned turning our staged opera into a film, I had no idea who would be willing to join this reimagined production,” Offerle said. “As it turns out, not only did everyone invited want to join the project, but they did so enthusiastically."

The Golem of Prague was made possible by Fine, Farkash & Parlapiano, P.A., Dr. Sally Ryden, Jim and Sharon Theriac, Vince and Jennifer LaRuffa, and supporters to the Elizabeth Graham Fund for Opera.

View the live stream recording online to watch the opera.